Tin Street was diagnosed at the age of 13 in 1988. He recalls that he had been getting taller and skinnier over a period of about 18 months and had been going off a lot of foods. He remembers visiting friends to play but not been able to keep up with them, “I also knew where all the toilets and taps were in town.”

His sister saw a show on TV where someone had diabetes and mentioned it, then his father talked to a friend who was a GP who suggested they got hold of some urine sticks for a quick, non-invasive test. Street remembers this well, “I pee’d on the stick and it changed to a deep, dark colour. I remember is almost being black.”

This meant that his blood glucose was extremely high, virtually off the scale. He went to school the next day as usual but, having received further advice on that result, his parents turned up at the gates and took him off to hospital. “By some miracle it was not diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), but I still spent five days in hospital getting stabilised. I instantly felt better after taking insulin.” I

Street remember a nurse coming up to me with an orange in her hand and a syringe with a needle on it and asking him if he wanted to practice on the fruit. “I said no and proceeded to give myself my first injection. When I went home, I was taking two injections daily and ‘eating for the insulin’ at certain times of the day as well as before exercise. The whole family learnt about carb exchanges, which I do think made things easier. Looking back, I feel lucky that I was resilient and that my parents helped me to take control of my own care. I never felt I had to hide my condition. Everyone knew I needed to have a Mars Bar before playing rugby!”

Street’s life

This regime continued for about five years before Street moved on to multiple daily injections (MDI) when he was 16 or 17. He says, “In the early 1990s my HbA1c remained stable at about 6.3mmol/L and everyone involved in my care, including my parents and myself, felt that ‘if it isn’t broke, don’t fix it’. It was about this time when I got my first blood test meter, which was by Accu-Chek.”

While going to school Street attended clinic in the local hospital in Boston, Lincolnshire where he’d been originally diagnosed. He went to university in Warwick and attended the nearest clinic to there, at Coventry & Warwickshire Hospital. He says, “I suppose it helped that I did a degree in engineering; diabetes is about numbers, and the numbers made sense to me. Having said that, I nearly came a cropper right at the end of university. I was out celebrating after finishing exams and forgot to take an injection; I ended up with DKA. Is the one time it’s ever happened to me and I swore never, ever again. It was not nice at all.”

After university, Street started his working career and the diabetes was just part of it all. “By this stage my HbA1c was around 7.5% but stable,” he says, “I’d work fairly solidly then be able to take a month off at a time. I’d go somewhere overseas, one time it was Greece, another time it was California and northern Mexico, another time Thailand and Australia. All through this I was on MDI using disposible syringes and two insulins, a long acting and a fast acting.”

Later his work took him to Hampshire where he attended Frimley Park Hospital and moved on to Novopens. When my work took me to London, I started to attend St George’s Hospital in Tooting. I was having a pretty good time, probably living much as I did as a student. I rarely had any real problems with my control. For a period, I had been cycling to work but after a while I realised that I’d have a hypo about an hour after I got to work; I decided it wasn’t worth it so stopped the cycling.”

Bump in road

Things bumbled along until Street hit a bump in the road in 2007 when, during a regular eye check, he was told to go to Moorfields Eye Hospital A&E as the opthalmologist could see damage in the back of my eye. “That was really scary,” he says. “At Moorfields I was told it was ‘just background retinopathy’. That didn’t sound like ‘just’ anything! Also, at this time I was having problems overnight with control; one time my partner could not me wake up in the morning and she called an ambulance. That happened on one other occasion too. It was all becoming more of a trial. It was around this time that I discovered the forum on www.diabetes.co.uk. I looked around that for a while, just growing my understanding of other people’s experience of living with diabetes.”

Things bumbled along until Street hit a bump in the road in 2007 when, during a regular eye check, he was told to go to Moorfields Eye Hospital A&E as the opthalmologist could see damage in the back of my eye. “That was really scary,” he says. “At Moorfields I was told it was ‘just background retinopathy’. That didn’t sound like ‘just’ anything! Also, at this time I was having problems overnight with control; one time my partner could not me wake up in the morning and she called an ambulance. That happened on one other occasion too. It was all becoming more of a trial. It was around this time that I discovered the forum on www.diabetes.co.uk. I looked around that for a while, just growing my understanding of other people’s experience of living with diabetes.”

In 2010 Street was extremely relieved to be told that the retinopathy in his eyes had receded. “It was at this time I put my first post onto the forum,” he says, “It was distressing to read about how many people were struggling with the condition. The ‘internet of diabetes’ was a depressing place, yet my own experience had not been too bad. I’d lived a pretty good life, I’d won a Tae Kwondo competition, played cricket in Jamaica. I thought that having Type 1 should not stop anyone from achieving their ambitions.”

On the www.diabetes.co.uk forum he moved from contributing to being a moderator. He says, “I found I had to keep repeating the same things as many of the questions were on the same issues, asked by someone who’d not seen the earlier replies. It occurred to me that doing a blog could be a better way to do this. I’d put the answers up on there then link the repeat questions back to it, so I did not have to copy and paste the same answer again and again.

Social mobility

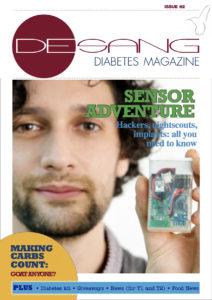

“I started my blog www.diabettech.com on 24 December 2014 when I reviewed the FreeStyle Libre. I was an early adopter of this novel technology and was curious about variations of data and experience that I was reading about online. I was prepared to undertake some sort of experimentation on myself. I would wear sensor but maybe change which insuIin I was using in order to see what effect it had on my control. The Libre sensor was a tipping point for me, leading to the blog and to what I do now, which is to write about insulin action and diabetes technologies.”

When he started his blog, Street wasn’t on Twitter or Facebook, that came about after he started blogging and when, also in 2015, he became involved in GB.DOC (where DOC see stands for diabetes online community not, for any Americans reading, the Department of Correction). He says, “I think I started on social media just before it became the crest of a wave. It probably helped that my Twitter handle was @Tims_Pants, which stood out.”

How does Street see social media now? “There are upsides and downsides to using social media. The downside is that people can be judgemental and even abusive, ‘keyboard warriors’ about their viewpoints. The upside is that you can meet more people who are dealing with the same things that you are, and that can help. Not only is there a sense of community but you may pick up tips or things to think about. There might be 50 people in a forum and any one time. There’s a great sense of sharing and sometimes these lead to face-to-face get-togethers, a meet up down a pub.”

The science of one

As the blog continued and gained a following, Street started to try to do his home experiments in a more quantitative way. “I used N=1, which is way to say that the experiments were being done only on one person, myself,” he explains, “Therefore, I would only deliver and analyze one set of results, not at all like a trial where you might have many people involved and the results would be aggregated and given as averages. Is it scientific? I tried to take a statistical and analytical approach, setting each one up as a project to capture the data. Then I use analytical tools to try to assess what is learnt and what further questions there may be as a result. I try to put in a consistent approach using traditional mathematics as well as my imagination.”

Is this kind of approach and attitude that has led to other people with diabetes creating ‘DIY looping’, also known as Open APS (artificial pump system). Street says that there is a misconception that this is hacking, but that it’s not. “Hacking is associated with cybercrime, cracking passwords, doing illegal things and gaining unauthorised access to systems such as those of banks or governments. This is illegal exploitation of a computer system for dubious aims,” he says.

DIY looping came about when users with a mind for this kind of thing realized that some CGMs deliberately had an open signal, which a relevant device could listen out for, read the data, store it and even present it as graphs for easier understanding. It led to the #nightscout and #wearenotwaiting movement. “So, it’s not hacking, just picking up the CGM signal,” he says. “Other people with an interest in science, engineering and their own diabetes were figuring out how the technology worked, how it communicated. Nothing is broken into.”

We interviewed another early user of Open APS in 2017, Tim Omer [issue 82, Sept 2017]. In March 2016 Tim Street met Tim Omer and they built their own Open APS in August 2016. Says Street, “It’s really a matter of understanding the protocols involved in order to intervene to tell the pump to do the same things – like carb count or bolus advise – but personalize it in order to better control the outcome, i.e. to gain even better control.”

Back when we met him, Tim Omer argued that we’re all taking risks every day with our diabetes care. Each decision we make (or guess) for delivering a bolus or counting carbs or whether or not to do any exercise comes with a risk. Similarly, Street says, “Insulin dosing is already a huge risk as you are handling a potentially lethal drug. Commercial companies will tell you a lot about the product but you’re not going to hear as much about what it’s actually like to use it or necessarily see anyone’s real data.

“DIY looping and Open APS may sound like they are cobbled together, but in fact we used standard operating system checks and test the codes before it is released. It is a rigorous testing process and therefore not risky, plus it can still be tweaked and amended by the user. It means that I understand what I’m changing and why.There is inherent risk is in living with Type I diabetes. I don’t’ feel that using the tools on hand to make my own control the best it can possibly be is a risk, and I share what learn. If others find that interesting or insightful, then great.”

See Tim Street’s blog here: www.diabettech.com